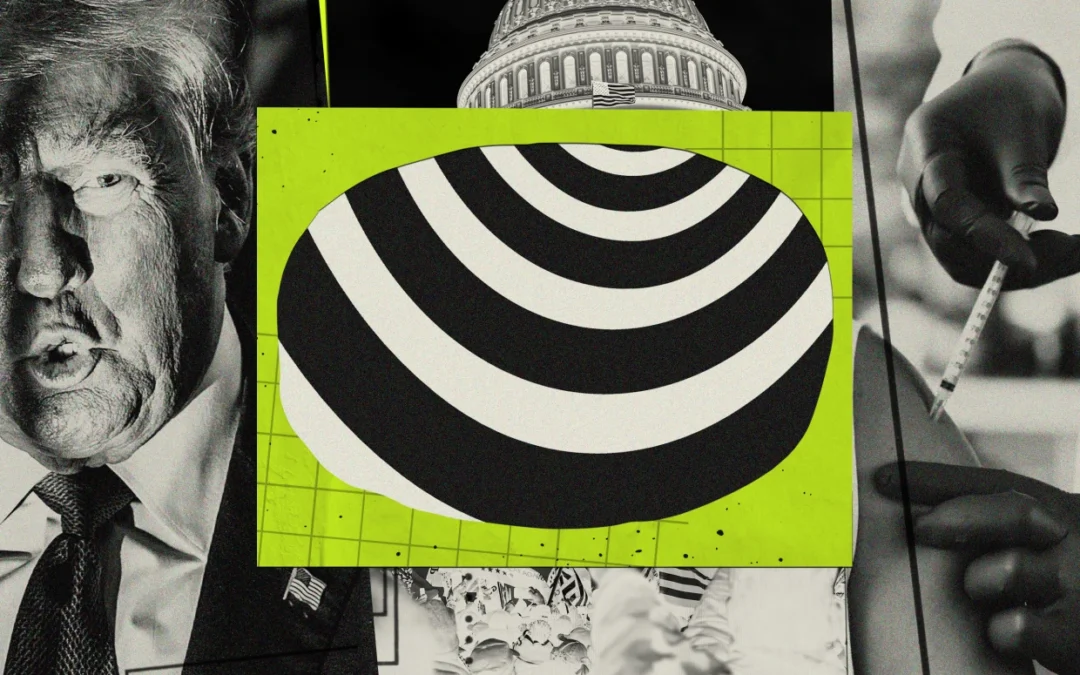

The U.S. presidential election comes at a time of ideal circumstances for disinformation and the people who spread it.

Disinformation poses an unprecedented threat to democracy in the United States in 2024, according to researchers, technologists and political scientists.

As the presidential election approaches, experts warn that a convergence of events at home and abroad, on traditional and social media — and amid an environment of rising authoritarianism, deep distrust, and political and social unrest — makes the dangers from propaganda, falsehoods and conspiracy theories more dire than ever.

The U.S. presidential election comes during a historic year, with billions of people voting in other elections in more than 50 countries, including in Europe, India, Mexico and South Africa. And it comes at a time of ideal circumstances for disinformation and the people who spread it.

An increasing number of voters have proven susceptible to disinformation from former President Donald Trump and his allies; artificial intelligence technology is ubiquitous; social media companies have slashed efforts to rein in misinformation on their platforms; and attacks on the work and reputation of academics tracking disinformation have chilled research.

“On one hand, this should feel like January 2020,” said Claire Wardle, co-director of Brown University’s Information Futures Lab, who studies misinformation and elections, referring to the presidential contenders four years ago. “But after a pandemic, an insurrection and a hardening of belief that the election was stolen, as well as congressional investigations into those of us who work in this field, it feels utterly different.”

The threat disinformation poses falls on a spectrum. Research suggests it has little direct effect on voting choices, but spread by political elites, especially national candidates, it can impact how people make up their minds about issues. It can also provide false evidence for claims with conclusions that threaten democracy or national health, when people are persuaded to take up arms against Congress, for example, or decline vaccination.

Solutions for the enormity of that threat are piecemeal and distant: the revival of local news, the creation of information literacy programs, and the passage of meaningful legislation around social media, among others.

“Repairing the information environment around the election involves more than just ‘tackling disinformation,’” Wardle said. “And the political violence and aftermath of Jan. 6 showed us what’s at stake.”

Primed for disinformation

The most likely Republican presidential nominee is also the former president — whose time in office was marked by lies told in a failed effort to remain there, falsehoods Trump continues to cling to. Disinformation in service of the lie that the election was “stolen” — disseminated through a network of television, radio and online media — has proven staggeringly effective with Republicans. The toll from that belief extends to distrust in future elections.

On one hand, real consequences have come for spreaders of disinformation. Lies about Covid and the election have reportedly cost some prominent doctors and news anchors their jobs. Millions of dollars have been awarded in civil courts to victims of disinformation. Hundreds of federal criminal convictions have come from the Jan. 6, 2021, riot. And people who allegedly participated in a scheme to overturn President Joe Biden’s victory, including state GOP officials, lawyers and Trump himself, face criminal charges.

Whether networks like Fox News or individuals like Rudy Giuliani would be as eager to promote disinformation in 2024 in the face of such consequences remains to be seen. But some predictable players and newcomers in right-wing media have already signaled a willingness to contribute.

“Right-wing media see a demand for content that is pro-Trump and leaning into conspiracy theories,” said A.J. Bauer, an assistant journalism professor at the University of Alabama who studies conservative media.

In addition to national websites known for disinformation, new local hyperpartisan news organizations might also factor in, Bauer said, with claims acting as fodder for larger national conspiracy theories.

“These outlets could be looking for examples of hyperlocal voter fraud or intimidation, even if it’s not real,” Bauer said.

Real stakes

It’s not only voters, but smaller loci of influence made up of state lawmakers, election officials and poll workers moved by disinformation who stand to affect the upcoming election.

“Election denialism and the misinformation that comes from the far right was in clear view on the federal level” with the 2020 election, said Christina Baal-Owens, executive director of Public Wise, a nonpartisan voting rights organization that tracks local election administration officials who have questioned the legitimacy of the 2020 election. “What was less clear was a threat that was hiding in plain sight, a movement working on the local level.”

Public Wise has counted more than 200 people who attended, funded or organized the Jan. 6 attempted insurrection and won office in 2022. In Arizona alone, more than half of constituents are represented by state legislators who are professed election deniers.

“We’re looking at a well-organized movement that is working to affect elections across the country,” Baal-Owens said. “They have the ability to determine how people vote, how votes are counted, and whether or not they’re certified.”

The Capitol breach was the most visible example of political extremism bleeding into real-world violence. But 2020 was also marked by violence, or the threat of it, at state capitols and Covid lockdown protests, a trend experts fear will continue.